Are learning styles a myth or valid?

You’re probably familiar with the concept of learning styles. Throughout school, you might have heard that people learn better when the materials match their learning style. If you’ve ever done any teaching or tutoring, you might have even attempted to tailor the work to your students’ learning styles. Intuitively, this seems to make sense. As we’re told, there are visual learners, aural learners, experiential learners, kinesthetic learners, and so on...or are there?

What you may not realise is that there is a long-running debate in the education sector suggesting that learning styles are a myth. According to many psychologists, education professionals, and neuroscientists, learning styles are one of the most prevalent ‘neuromyths’. That is, a false idea about how the brain works or learning occurs. They’re no more real than bigfoot, or another popular neuromyth — the misconception that we only use 10% of our brains. Some sources even take this a step further, saying that “believing in learning styles has been compared to believing in fortunetelling.”

So, with a mounting body of evidence suggesting that learning styles are a myth, we’ll dig deeper to ask if learning styles are a myth or valid. We’ll start by deconstructing the learning styles myth, examining the popularity of learning styles, before looking at studies into learning styles and finally asking once and for all: are learning styles a myth?

This article will be the first in a two-part series on learning styles. Be sure to check back in a fortnight when we ask: ‘What should L&D teams be using instead of learning styles?’

Deconstructing the learning styles myth

According to a wealth of research and empirical evidence, there are no two ways about it: learning styles are a myth. Anyone who’s grown up believing in learning styles might find this surprising. You might even think of yourself as having a particular learning style. So, what does this mean? Let’s dig into these findings and deconstruct the myth of learning styles.

The popularity of learning styles

The idea of different ‘learning styles’ began to gain traction in the 1970s and has since become pervasive in education worldwide, with many educators trying to use learning styles to their advantage.

These days, 93% of UK schoolteachers agree with the statement: “individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style.” Similarly, a study of higher education providers in the USA found that 64% agree that teaching to a student’s preferred learning style enhances learning.

Further, a study of over 15,000 educators worldwide found that 89.1% believe that people learn better when instruction is matched to their learning styles, while 87.8% believe in learning styles in general.

So far, this makes sense. Most of us are probably familiar with learning styles as a concept and received some education centring around learning styles at school or university. However, this begs the question, if learning styles are a myth, how did they become so popular?

Dr Shaylene Nancekivell, who recently conducted a study into learning styles for the Journal of Educational Psychology, offers a relatively straightforward explanation for this question: learning styles fit with how we like to perceive learning.

“It seems likely that the appeal of the learning styles myth rests in its fit with the way people like to think about behavior. People prefer brain-based accounts of behavior, and they like to categorise people into types. Learning styles allow people to do both of those things," she explains.

In many ways, this is another example of why cookie-cutter training doesn’t work. People are nuanced and defy easy categorisation, while learning is a complex, ongoing journey. It’s not as simple as saying ‘I’m X type of learner’ and always approaching learning that same way. Rather, learning is fluid and highly contextual, with the ideal learning style changing depending on the situation and subject matter.

Dr Nancekivell adds that she is concerned learning styles “teach young children maladaptive strategies for learning”, noting that they can often do more harm than good.

Are learning styles a myth?

Now that we understand the prevalence of learning styles and how this came to be, it’s time to move on to the big question: are learning styles a myth?

Many reputable sources are unequivocal on this topic: learning styles are a myth. Following countless studies, there is no empirical evidence to suggest people learn any better when the subject matter is tailored to their ‘learning style’.

As PopSci puts it, “the evidence has been mounting that a curriculum tailored toward a specific learning style isn’t any more effective than just, well, teaching.”

Likewise, a 2006 study by researchers Kratzig & Arbuthnott concluded that “[learning styles] are commonly justified in terms of brain function, despite educational and scientific evidence suggesting that the learning style approach is not helpful.”

A 2017 study published in Frontiers in Psychology corroborates these findings, adding, “this idea [learning styles] has been repeatedly tested and there is currently no evidence to support it.”

The British Psychological Association Digest takes this a step further, summarising that research shows earners don’t benefit from their preferred style, teachers and students have different ideas about what learning styles work for them, and we have little insight into how much we’re actually learning from various methods.

Finally, research by the American Psychological Association puts it in no uncertain terms, saying, “there is no scientific evidence to support this common myth [of learning styles].” Quite the opposite. Their findings suggest that belief in learning styles may be actively detrimental to learners, saying, “previous research has shown that the learning styles model can undermine education in many ways.”

As such, the answer is clear: yes, learning styles — at least in the way that we currently interpret and understand them — are a myth.

Learning style studies

You may be thinking, these quotes are well and good, but if learning styles are a myth, where’s the proof? Thankfully, there have been numerous studies conducted on the topic of learning styles. We’ll take you through a few of them now.

Downsides of learning styles

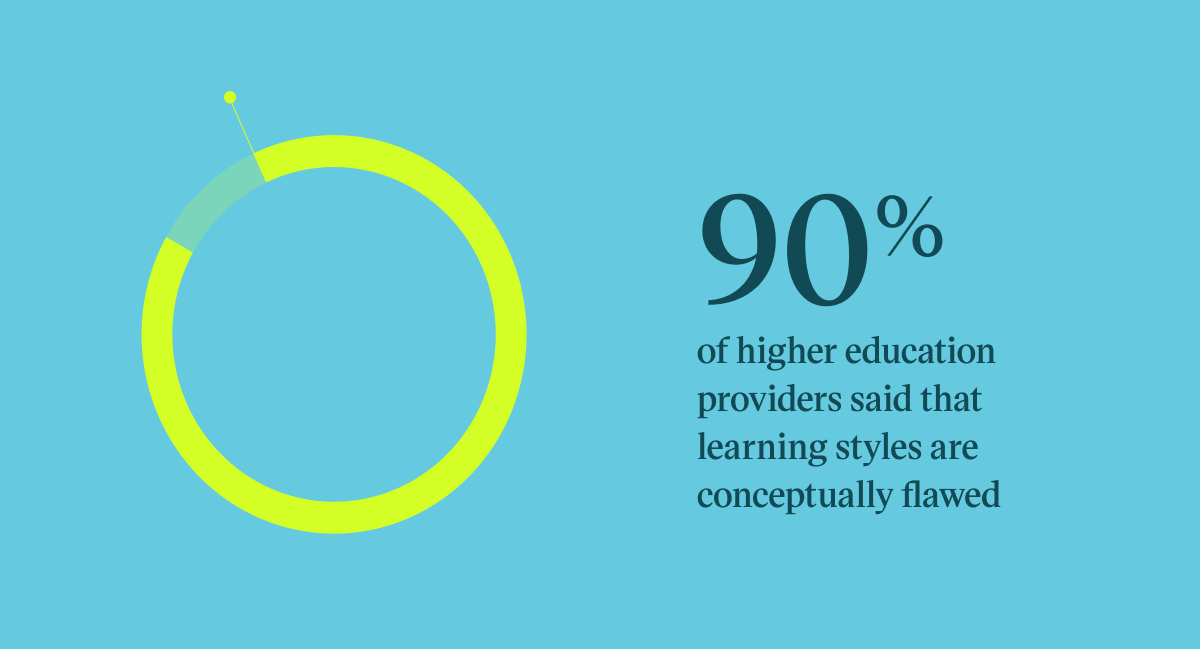

In a study of more than 100 higher education providers in the UK, 90% said that learning styles are conceptually flawed. Plus, 67% believe they pigeonhole learners, 61% think they waste resources, 56% think they create unrealistic expectations, and 48% think they are driven by profit, not helping learners.

What’s more, before completing this study, 64% of participants said they plan their lessons to accommodate learning styles. However, after participating in the study and seeing evidence to the contrary, this figure halved to just 32%.

On the other hand, 64% agreed that participating in the study helped them understand the lack of evidence to support using learning styles.

Undergrad study

In another study published in Anatomical Sciences Education, researchers encouraged hundreds of undergraduate students to take a popular online learning styles quiz and then “adopt the study practices consistent with their dominant learning style.” The results were eye-opening.

First of all, they found students’ grades did not correlate in any meaningful way with their dominant learning style, nor any learning style(s) they scored highly on.

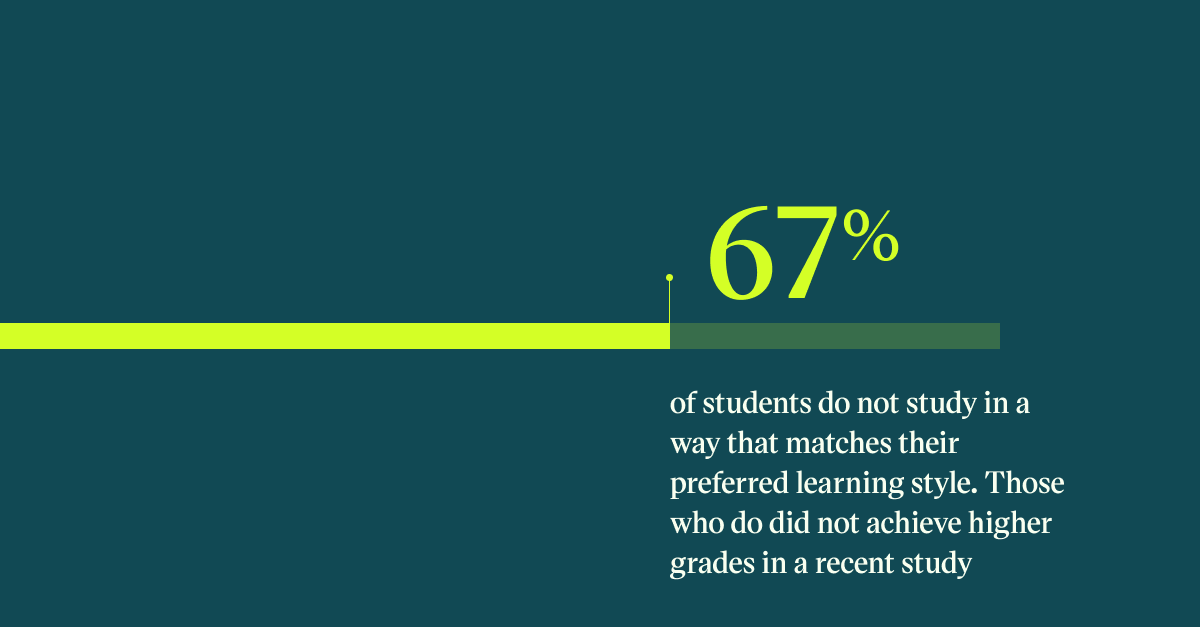

Further, 67% of students do not study in a way that matches their preferred learning style. Those who do study in a way that matches their preferred learning style did not achieve higher grades.

Ultimately, the researchers concluded that this study “provides strong evidence that instructors and students should not be promoting the concept of learning styles for studying and/or for teaching interventions. Thus, the adage of ‘I can’t learn subject X because I am a visual learner’ should be put to rest once and for all.”

Do visual learners remember pictures better?

Further studies have yielded similar results. One study, published in the British Journal of Psychology, tested students' visual and verbal memories.

Students with an aural learning style thought they’d remember the words better, while students with a visual learning style thought they'd remember the pictures better. Nevertheless, researchers found no correlation between students’ preferred learning styles and their memory. In other words, so-called visual learners did not remember pictures better, nor did aural learners remember words better.

A similar study, published in the Journal of Educational Psychology, “found no relationship between the study subjects’ learning-style preference (visual or auditory) and their performance on reading or listening-comprehension tests. Instead, the visual learners performed best on all kinds of tests.”

If not learning styles, then what?

These studies are only the tip of the iceberg. Over the years, there have been numerous studies conducted into learning styles, with few returning any compelling evidence that learning styles are useful for learners.

However, this does not mean that learning styles should be dismissed entirely. We don't want to throw out the baby with the bath water, as there is still some validity to the idea that learners have different preferences — just not in the way that we currently understand learning styles.

As Education Next explains, “the belief in learning styles stems from an incorrect interpretation of valid research findings and scientifically established facts. For example, it is true that different types of information are processed in different parts of the brain. It is also true that individuals have differences in abilities and preferences.”

So, how do we make learning stick? Should we still be trying to accommodate different learning styles in the workplace? Does technology impact learning styles? We’ll go into all this and more in the second part of our learning styles series in a fortnight, where we ask: ‘What should L&D teams be using instead of learning styles?’

For more insights, be sure to subscribe to the Go1 newsletter to stay on top of all the latest L&D trends. Or, you can book a demo today to find out how Go1 can help with your team’s learning needs.